There are places you go to for great barbecue, sun and sand or monstrous surfer swells. There are places like Tagaytay or Boracay where you don’t need a map to traverse routes and roads. Even a 7-year old knows the whole loop.

Matnog is not one of those places.

It’s a place where the oldest of Daragenos live (ours included), and those lost simply pass it by en route to famous destinations like Legazpi, Cagsawa Ruins or any other spot in Daraga.

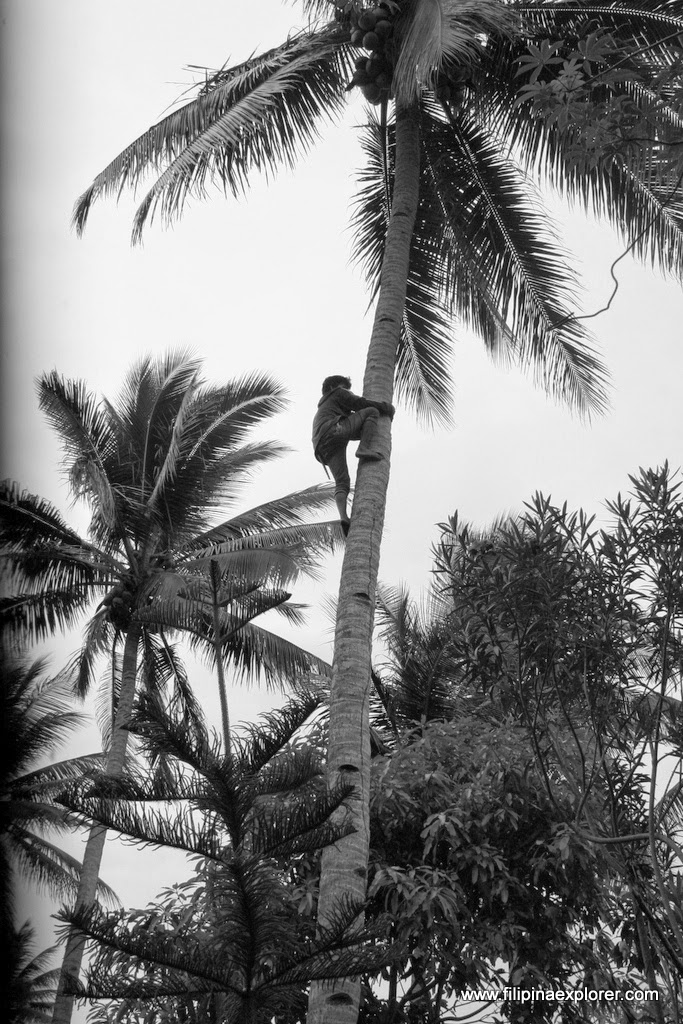

It’s one of those little-known towns burrowed deep in greens, the scent of burning leaves and soot in cold mornings, the early putting out of lights by dusk. Where people play basketball at the plaza, watch cockfights, toil in their yards, or listen to the radio to pass time. Where coconut trees outnumber people, and townsfolk stop on their tracks when a car passes by.

Summer afternoons here are spent on a hammock over dirt grounds, where I learned to listen to an old woman’s stories of war, early marriage and rural life in a peculiar language. My grandmother, beautiful even in her wrinkly 50s, huffing and puffing a cigarette as she delivers what seems to be vowels strewn with endless strings of Rs. Despite my hardest, I am unable to adopt the dialect, leaving me often clueless of stories told, including those about me.

Yet I continued to listen and nodded as if I understood. She spanks my back lightly when after all that blabbering I tell her I do not speak Bicolano. Still, each time we visit she retells stories in the language she knows best.

For the next four-and-a-half days, I relive those lone still afternoons on my grandmother’s porch, now cemented like the many homes and dirt roads that have slowly adopted to change over the decades.

What doesn’t change though is Matnog’s unique place on the map: the very feet of ferocious Mayon Volcano. With eruptions, lava flow changes course depending on which is the deepest volcanic spillway. For many eruptions Matnog has been lucky the spillway it sits on doesn’t happen to be the deepest yet.

Had it not been so lucky, I probably wouldn’t be here, slurping on freshly picked young coconuts with my daughter, listening once again to stories in strange-sounding tongue.

|

| Early morning cockfight. |

|

| Fresh coconuts just after picking! |

I didn’t think my grandmother and I had anything in common. She even hates the way Lia throws tantrums. “Maribukun. Pasawayun na sana!” She’s loud and spoiled, she says, and none of her kids were like that because they were spanked the very instant they started whimpering.

But as she cried bidding Lia and me goodbye at the airport, I thought, maybe we had something in common after all. Sometimes, when you listen intently enough, you’ll find you can speak an inner language that transcends spoken ones.

We are women rooted in the same history, generations upon generations of tales as rich as the black slope of volcanic earth from where they spring forth.

I placed Lia on her seat by the window, anticipating the worst, this being her first plane ride. But as the plane took off and sailed in the sky, she got up her seat, smiled and pointed at Mayon. She wouldn’t remember it, but she was happy as if she truly belonged since we sprinted off the highway to Bicol. And she doesn’t speak Bicolano either.

We all have something in common after all.

|

| At 2,000 feet in an air taxi. Till we meet again, Mayon. |